by Mitch Hauschildt, MA, ATC, CSCS

Working at a DI university athletic department, we order a LOT of MRIs. We order them for a variety of reasons. Usually we order them to look deeper into an injury for diagnostic and treatment purposes. Sometimes we order them to track changes over time. Sometimes we order an MRI because insurance companies require them prior to a specific procedure. Sometimes we order them to demonstrate that there is no tissue damage in an area. And, at times we order them to make coaches, parents or athletes happy and feeling as though we are taking them serious.

The problem that we have with MRIs in our culture is that people have unfortunately been lead to believe that an MRI is a fix or a cure for an injury or illness and that they are foolproof. Neither are true.

We have to remember that an MRI is a test. It is a scan of issue. An MRI looks for structural damage that may explain why someone has pain or dysfunction. It is a picture, just like an X-ray, CT scan, bone scan, or picture on your phone. All of these can be used to gather information which may guide our treatments, but an MRI is not a treatment itself. Sometimes it explains why someone is having pain, but many times it does not. We understand from research that there is actually very little connection between tissue damage and pain. So, some people will have very dramatic MRI images, showing lots of tissue damage, but no pain. Others will have a lot of pain, but their MRI will be clean. This can be frustrating for both the clinician and the patient.

We also have to be very careful when we interpret MRI results. I actually cringe many times when I hear that someone is having an MRI, because many times things show up that don’t matter, but when those things are known, it can really muddy the treatment waters. As an example, there are multiple studies showing that the majority of people in the US have a disc herniation in their low back, but no pain. So, if you get an MRI on your low back, it is likely to show some sort of a pathology. Does that pathology matter or not?? This is where things get awful muddy.

The accuracy of an MRI is also very dependent on who reads the scan and how it is correlated with a clinical exam. I recently came across a social media post from Mike Reinold where reviewed a research article regarding the accuracy of MRIs. It peaked my interest, so I looked further into it.

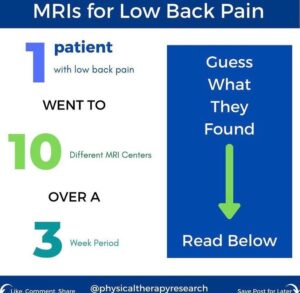

The article, published in The Spine Journal, looked at a 63-year-old female patient who had a history of low back pain and L5 radiculopathy. She had 10 MRIs at 10 different MRI centers over a 3 week period. Each scan was read by a different radiologist. What they found was interesting in that there was a large variability in the results of the MRI depending on where the MRI was performed and who read the scan. The highlights of the results are as follows:

- There were 49 distinct findings among the 10 MRIs

- 0 of the 49 findings were reported in all 10 MRIs

- There was only 1 finding that was reported in 9 out of the 10 MRIs

- 32% of the findings appeared only once across all 10 MRI reports

- The average true positive rate (sensitivity) was only 56.4%

We need to keep in mind that this is just 1 patient and 1 body part, so she may have some challenging issues or anatomy that make this a unique situation. So, I don’t want to make this an over generalization of all MRIs on all areas of the body. But, if there is this much variance on 1 patient across 10 MRIs, it has to make us question the validity and usefulness of an MRI.

We know that for most patients and more information is a good thing, so an MRI is typically useful. But, we need to make sure it is read by an experienced MSK radiologist or surgeon and correlated with a clinical exam. I prefer to have MRIs read by a specific radiologist that is very experienced with MSK scans and then also read by the ordering physician to correlate it with what they are seeing clinically. This puts some checks in place to make sure we are all seeing the same things. I also prefer to discuss the results of the MRI with the physician prior to the patient being learning of the results. This allows us to game plan the treatment process and be on the same page with what is most important for that patient to know and understand at that time.

What does it mean for clinicians?

As a clinician working with patients who often come to me after having had an MRI or interested in getting an MRI, I spend a lot of time educating my patients. I work hard to educate them on what their MRI actually means or why they shouldn’t just jump to an MRI because it may actually make the treatment and recovery process more difficult. Once a seed is planted in the mind of a patient, it can be very difficult to back things out. Educate. Educate. Educate.

Conclusion

MRIs are very useful tools for the a lot of the injuries that we treat everyday. Unfortunately, they aren’t a cure-all and they can actually make things more difficult for the patient to understand what is going on. We should be quick to educate and slow to push our patients towards an MRI. When MRIs are indicated, make sure the read is coming from a trusted source and correlated with clinical findings. Finally, make sure that your patients fully understand what an MRI is and is not and why and when they should be used.

Reference:

Richard Herzog, Daniel R. Elgort, Adam E. Flanders, Peter J. Moley,

Variability in diagnostic error rates of 10 MRI centers performing lumbar spine MRI examinations on the same patient within a 3-week period,

The Spine Journal,

Volume 17, Issue 4,

2017,

Pages 554-561,

ISSN 1529-9430,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2016.11.009.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1529943016310932)

Leave a Reply