by Mitch Hauschildt, MA, ATC, CSCS

I train mobility a lot with my patients. It is important that we have access to the range of motion that is required to get into the positions that we desire. I do think that mobility is often trained incorrectly or at the wrong time and often gets blamed for dysfunction that isn’t warranted. After all, just because someone “can” do something, it doesn’t me that they “will” do it when under pressure or not thinking about it. But, all of that is another blog post in and of itself.

Most of us think of a mobility issue as either in a joint or in a muscle, but it is actually much more complex than that. I was taught in school that most tissue restrictions are due to scarring or fibrosis, but the latest research just isn’t supporting that concept.

What the research does support (as well as clinical expertise) is the notion that all restrictions are either mechanically or neurologically driven. You may be thinking, “that’s not ground breaking!” And, you would be correct. But, just like it is easy for people to say that “everything starts with the core” even when they have no actual idea what that means or how core dysfunction actually affects the rest of the system, it is easy to say that things are either neurologically or mechanically driven without really understanding how it affects our movements.

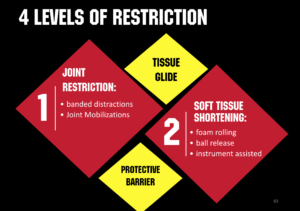

To break things down in an effort to fully understand how and why restrictions occur, we are going to look deeper into the 4 different types of restrictions.

- Joint Restriction: The SFMA guys would refer to this as a JMD or Joint Mobility Dysfunction. This type of restriction is due to a mechanical shortening of the tissue surrounding a joint, or a change to the tissue within the joint. This includes a joint capsular shortening, which oftentimes occurs after a period of immobilization or non use. You may also find joint restrictions in people who have a cartilage tear or a subluxation of some sort. Joint restrictions respond best to joint mobilizations and distractions. Anything that begins to move the joint and stresses the capsule will work well to free up this restriction. Typically a joint restriction will take time to correct over a series of multiple visits.

- Soft Tissue Restriction: The SFMA guys would call this a TED or a Tissue Extensibility Dysfunction. This is when someone is “tight.” Most of us were taught in school that this is also a mechanical restriction due to soft tissue that is resistant to being stretched. The reality is that this is a nervous system response. Someone who is “tighter” than someone else just has a nervous system that is more sensitive to a stretch sensation than someone else. That’s why I actually prefer the term “stretch tolerance” instead of flexibility. Improving someone’s soft tissue restriction involves down regulating nervous system tone in order to allow they to move further and with greater ease. We MUST understand that muscle is muscle. It is essentially the same tissue from one person to the next. Our brain decides how “tight” we are. In order to make some headway here, we need to combine soft tissue work (i.e. IASTM, foam rolling, massage) with stretching and then exercise to lock in the improvements. Static stretching alone rarely makes a meaningful difference with soft tissue restrictions.

- Tissue Glide: Tissue glide is one of the non-typical restrictions on this list. A lot of people don’t consider lack of tissue glide when looking at mobility but it oftentimes plays an important role in how far a person can move through a range of motion. When the various layers of fascia, skin and muscle don’t slide and glide over top of each other efficiently, they will restrict range of motion. As Dr Geoffrey Bove says of fascia, “Its all about the interfaces. Lack of glide is the enemy.” Typically where there is a lack of tissue glide, it has something to do with Hyaluronic Acid (HA) and poor viscosity and/or compressed tissue. Decompressing tissue and improving (HA) viscosity is the key to improving in this area of movement.

- Perceived Threat: When the brain is threatened by something going on in the body, it oftentimes limits range of motion in order to minimize any further damage. It is important that we understand that this is a perceived threat and not an actual threat. When the brain limits range of motion, it is in response to something that may or may not actually be taking place. That is why we always want to evaluate range of motion actively and passively and in different postural positions. If range of motion changes in different conditions, it is a neurological response, not an actual loss of motion. The key here is taking the brain off of threat. There are a number of ways to do that, but my favorite includes IASTM, vibration, dry needling and kinesiology taping. Anything that will change the feedback into the brain will be impactful.

It’s important that we look for all 4 of these types of restrictions when we evaluate our patients and clients. Failure to do so will result in poor outcomes and oftentimes lots of pain and frustration on the part of the people that we are working with. You can’t prescribe the right interventions if you don’t know what it is that you are treating.

Is one more important than the rest?

This is a valid question and my initial response is no, because they are all important and need to be addressed. However, I do firmly believe that if a neurological threat exists and if it is left untreated, it will lead to one or more of the other 3 mobility issues. What I see in my clinical practice is that if the neurological threat is left long enough, tissue shortening takes place, glide becomes restricted and the brain becomes more resistant to a stretching sensation as it works to protect the area.

So, I don’t know that dealing with a neurological threat is more important than the other 3, but it is likely the root cause of most mobility issues. An example of this is the post surgical patient. When they enter the operating room, they usually have full or near full range of motion in the joint that they are having worked on. But, a couple of hours after surgery when they come out of recovery, they suddenly can’t move. This doesn’t mean that magically in a few short hours that they laid down a bunch of scar tissue or had a capsule shrink (unless that is the goal of the surgery). What it means is that the brain is threated by the traumatized area and that threat will cause it to lock things down. If left for days or weeks without movement, then we start to see tissue shortening, poor glide and so on. Managing threat is the way to improve post surgical range of motion.

The older I get, the more I am convinced that we are constantly treating the brain. We may think that we are treating local tissue, but for the most part, it is the nervous system that is treated.

Leave a Reply