The “core” has become one of the hottest topics in the fitness and sports medicine world over the past decade. It is often an overused term that actually causes more confusion than clarity in a lot of situations. The term is usually intended to describe the area in the center of the body which encompasses the abdominal muscles, low back muscles, and many times the muscles of the hip, including the glutes, ab/adductors, and hip flexors.

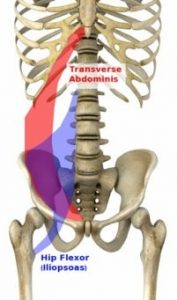

In this conversation, we will use the term “core” to describe the muscles of the abdomin and low back which are primarily responsible for stabilizing the pelvis. These are the Transverse Abdominis and Multifidus muscles. They are very deep within the abdominal cavity and are very difficult for many of today’s athletes to engage.

In this conversation, we will use the term “core” to describe the muscles of the abdomin and low back which are primarily responsible for stabilizing the pelvis. These are the Transverse Abdominis and Multifidus muscles. They are very deep within the abdominal cavity and are very difficult for many of today’s athletes to engage.

When an athlete isn’t able to engage the core to stabilize the pelvis, there are a great number of issues that can arise. These issues are both performance degregation and injury. One major downfall that often occurs when the Transverse Abdominis and Multifidus aren’t working properly is the that hip flexors are forced to work overtime to help stabilize the pelvis. While they are intended to work synergistically to flex the trunk and femur, the hip flexors are not intended to stabilize the pelvis. When they become synergistically dominant, either injury or performance degregation will occur.

A prime example of when this occurs is during an active straight leg raise. On the surface, the test gives us an idea as to how flexible the athlete is in their hamstrings. This is true to a certain extent because if an athlete has an extreme hamstring mobility issue, it will show up in this movement. However, the hamstrings are the only muscles that can be evaluated with this test.

If an athlete is tight in the hip flexor in the leg which is on the floor, they will also be positive for an active straight leg raise. This is because the hip flexor will put the pelvis in an anteriorly rotated position, putting the hamstring on prestretch, and making the hamstrings appear to be less flexible than they really are.

If an athlete is tight in the hip flexor in the leg which is on the floor, they will also be positive for an active straight leg raise. This is because the hip flexor will put the pelvis in an anteriorly rotated position, putting the hamstring on prestretch, and making the hamstrings appear to be less flexible than they really are.

The third muscle group which can be evaluated during this movement is the core (which brings us back to the current topic). If the core is not firing properly to stabilize the pelvis, the hip flexors will turn on in an effort to make up for the core’s area of weakness. When the hip flexors activate, the pelvis rotates, the hamstrings appear “tight” and we have a positive test.

This same hip flexor dominance will show up in a number of other athletic positions as well. Somehow, the hip flexors have the ability to be dominant, weak, and innactive, all in the same athlete.

This same hip flexor dominance will show up in a number of other athletic positions as well. Somehow, the hip flexors have the ability to be dominant, weak, and innactive, all in the same athlete.

The key to preventing such an issue is training the inner unit of the core to be very active and stable. Proper core training will ensure that the athlete’s body understands when the hip flexor is supposed to work and when it is the core’s turn to turn on and stabilize.

Leave a Reply