by Mitch Hauschildt, MA, ATC, CSCS

by Mitch Hauschildt, MA, ATC, CSCS

For many years, I completely under appreciated the role of the proximal tibio-fibular joint. I was always lead to believe that it is pretty much a fixed joint that doesn’t have much of an impact on movement. Of course, just as with many other areas of the body, I was wrong on this. The proximal tibio-fibular joint, while not as impactful on movement as say the hip, knee or thoracic spine, can definitely change how we move. As with a lot of joints, too much movement isn’t usually good, and neither is not enough. Let’s explore a few ways that the proximal tibia-fibular joint affects how we move.

Too Much Laxity

Fibular head laxity can be assessed by grasping the proximal fibular head and performing an anterior-posterior glide. While not overly scientific, I consider excessive laxity as a translation of greater than 50% of the head of the fibula as compared to the resting position. If there is research out there establishing a standard for this, I have not seen it, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist, as I don’t consider myself a research geek by any stretch of the imagination. Pretty much everything in this post is based on my clinical experiences, so take them with a grain of salt.

Association with ACL tears

A few years ago, while working with a number of ACL patients, I noticed that many (approximately 40%) of my ACL patients presented with greater fibular head laxity on their involved leg as compared to their uninvolved leg. As I looked at it, my question became, what came first, the chicken or the egg? Meaning, did they have laxity in their tibio-fibular joint prior to tearing their ACL, making it a risk factor? Or, did they develop laxity as part of their mechanism of injury? So, I began to track fibular head laxity as part of our injury screens. I have tons of data, but the problem is that it takes a lot more than a ton of data to find an ACL tear or two at the college level (at least at our institution). Thus, I haven’t been able to find a strong correlation. I also reached out to a few researchers around the country who do a lot of ACL research and they are interested, but it takes a lot of resources to perform these types of studies and they are a little tapped out.

After a lot of observation, reading and thinking about it, my gut says that the fibular head movement that we see post ACL tear, is for some, a pre-existing condition and for others, part of their mechanism of injury. I do believe that there is a certain section of our population that has increased laxity which exposes them to an increased risk of ACL tears.

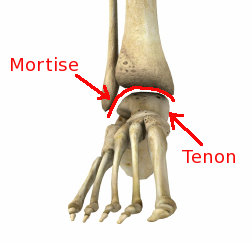

My theory goes like this…the most common mechanism for an ACL tear is foot pronation, tibial rotation and valgus at the knee. For most people, when the foot pronates, at some point it gets blocked and stopped by the distal fibula. When all else fails, it is the last resort. When someone has laxity at the tibio-fibular joint, the distal end of the fibula can’t perform this task effectively. Meaning, when they pronate, instead of getting blocked by the fibula, the fibula gets driven vertically and the foot continues to pronate. That excessive pronation starts a chain reaction that can’t be stopped at that point.

My theory goes like this…the most common mechanism for an ACL tear is foot pronation, tibial rotation and valgus at the knee. For most people, when the foot pronates, at some point it gets blocked and stopped by the distal fibula. When all else fails, it is the last resort. When someone has laxity at the tibio-fibular joint, the distal end of the fibula can’t perform this task effectively. Meaning, when they pronate, instead of getting blocked by the fibula, the fibula gets driven vertically and the foot continues to pronate. That excessive pronation starts a chain reaction that can’t be stopped at that point.

I don’t think that this is overly common and prevalent. And, I can’t prove it with research. But, there is enough there that I consider doing an intervention prophylactically for the athlete who competes in a high risk sport with some level of pronation and a grade 2-3 joint laxity.

I have found a correlation with patients who have distal IT band pain and proximal tibio-fibular joint laxity. This oftentimes occurs in distance runners and is diagnosed as “IT Band Friction Syndrome” or lateral knee pain. Both are incorrect.

When an individual bears weight on their foot, the foot is designed to pronate enough to absorb force and store energy to be recycled into the next action. When this occurs, the talus will bump up against the distal fibula. If the fibula isn’t fixed and solid, it will slide vertically. For many people, the brain realizes that the fibula isn’t as stable it would like it to be, so it fights to stabilize it. Because the IT band is right there, it begins to try to stabilize the joint and get it to stop moving vertically, thus stoping excessive pronation. The problem is, the IT band isn’t designed to do this. So, when it does it over and over, sooner or later it will become inflamed and painful.

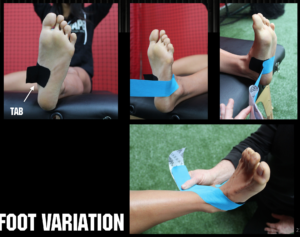

The solution to this problem is to prevent foot pronation from occurring. You can do this with some orthotics, or you can also use the Rocktape mid foot support taping technique with tabs. It is one of the few taping techniques that we teach with stretch on the tape, but we always use a “tab” with it, to minimize any risk of skin irritation. The more pronation you can stop for these patients, the better the outcome.

Not enough laxity

I prefer to have a small amount of movement at the proximal tib-fib joint. For some people with little to no mobility, it can limit ankle Dorsiflexion. In this situation, we are finding that performing an anterior mobilization with the fibular head can improve ankle mobility. My theory with this is that because the tibia and fibula are connected via connective tissue in the mid dle of the bone, that you can actually pivot the fibula back and forth at the ends. So, if you glide the proximal fibula anteriorly, in theory, it will push the distal end posteriorly. Considering the shape of the talus, when a distal fibula moves posteriorly, it opens the ankle up to more dorsiflexion.

dle of the bone, that you can actually pivot the fibula back and forth at the ends. So, if you glide the proximal fibula anteriorly, in theory, it will push the distal end posteriorly. Considering the shape of the talus, when a distal fibula moves posteriorly, it opens the ankle up to more dorsiflexion.

My preference when treating individuals with ankle restrictions that I believe is being at least partly driven by this dysfunction, is to perform an anterior joint mobilization to free it up and then lock it in with tweak taping over the fibular head, pulling it anteriorly as I lay the tape down.

If you are reading this and you have the opportunity to assess tibi0-fibular head laxity with your patients, I would appreciate your input and expertise. The more data and thought processes that we can have involved, the better we will get at confirming or refuting these theories. I’m happy to be disproven if we can find some good research and someone can teach me some clinical skills that help me and my patients improve more efficiently than what I have presented here. Until then, keep up the great work and take a look at the proximal tibio-fibular joint.

Hey Mitch,

Thanks for the article! I usually assess proximal and distal fib head motion upon injury, but haven’t done so preventatively. I’ve definitely seen the correlation between lack of dorsiflexion and fibular immobility (both proximally and distally). I’ve also seen the lack of proximal fib head motion as well as hypermobility as contributing factors to lateral knee pain.

I look forward to seeing more outcomes that you find!

Hi there mates, pleasant piece of writing and fastidious arguments commented at this place, I am in fact enjoying by these.

My husband recently had knee replacement. He is a tennis player with bone on bone and arthritis. As soon as he awoke from surgery, he said that he was still hurting in the same spot as before replacement. Now, the pain has been diagnosed as coming from the tib/fib joint. the knee replacement went exceptionally well, but this pain is hampering his improvement. Any suggestions would be extremely appreciated.

Sounds like he’s a bit of a challenge. I would start by looking at his foot. Does he pronate at all? If he does, I would try to stop any and all pronation with tape or an orthotic to see if it improves. The other issue that can come up in that area is that his peroneal nerve gets really irritated and causes pain. If that is the case, it is going to take a lot of time with limited activities to settle it down.

Any ideas how a layperson could go about discovering if they have too much or not enough laxity ?